Animal Behavior Researchers Often Refer

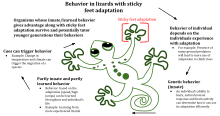

A range of brute behaviours

Alter in behavior in lizards throughout natural selection

Ethology is the scientific study of animal behaviour, normally with a focus on behaviour under natural conditions, and viewing behaviour every bit an evolutionarily adaptive trait.[1] Behaviourism as a term also describes the scientific and objective study of animal behaviour, usually referring to measured responses to stimuli or to trained behavioural responses in a laboratory context, without a particular emphasis on evolutionary adaptivity.[2] Throughout history, unlike naturalists take studied aspects of animate being behaviour. Ethology has its scientific roots in the piece of work of Charles Darwin and of American and German ornithologists of the late 19th and early on 20th century,[three] [four] including Charles O. Whitman, Oskar Heinroth, and Wallace Craig. The modernistic subject area of ethology is more often than not considered to have begun during the 1930s with the work of Dutch biologist Nikolaas Tinbergen and Austrian biologists Konrad Lorenz and Karl von Frisch, the 3 recipients of the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[v] Ethology combines laboratory and field scientific discipline, with a potent relation to another disciplines such every bit neuroanatomy, ecology, and evolutionary biological science. Ethologists typically show interest in a behavioural process rather than in a particular animal group,[6] and oftentimes report one type of behaviour, such as aggression, in a number of unrelated species.

Ethology is a quickly growing field. Since the dawn of the 21st century researchers have re-examined and reached new conclusions in many aspects of brute advice, emotions, civilization, learning and sexuality that the scientific community long thought it understood. New fields, such equally neuroethology, have adult.

Agreement ethology or animal behaviour can be important in animal training. Because the natural behaviours of different species or breeds enables trainers to select the individuals all-time suited to perform the required job. It also enables trainers to encourage the performance of naturally occurring behaviours and the discontinuance of undesirable behaviours.[7]

Etymology [edit]

The term ethology derives from the Greek language: ἦθος, ethos pregnant "character" and -λογία , -logia pregnant "the study of". The term was outset popularized by American myrmecologist (a person who studies ants) William Morton Wheeler in 1902.[eight]

History [edit]

The beginnings of ethology [edit]

Charles Darwin (1809–1882) explored the expression of emotions in animals.

Because ethology is considered a topic of biology, ethologists have been concerned particularly with the evolution of behaviour and its understanding in terms of natural selection. In 1 sense, the first mod ethologist was Charles Darwin, whose 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals influenced many ethologists. He pursued his involvement in behaviour past encouraging his protégé George Romanes, who investigated brute learning and intelligence using an anthropomorphic method, anecdotal cognitivism, that did not gain scientific support.[9]

Other early ethologists, such as Eugène Marais, Charles O. Whitman, Oskar Heinroth, Wallace Craig and Julian Huxley, instead full-bodied on behaviours that tin be chosen instinctive, or natural, in that they occur in all members of a species under specified circumstances. Their commencement for studying the behaviour of a new species was to construct an ethogram (a clarification of the main types of behaviour with their frequencies of occurrence). This provided an objective, cumulative database of behaviour, which subsequent researchers could bank check and supplement.[8]

Growth of the field [edit]

Due to the piece of work of Konrad Lorenz and Niko Tinbergen, ethology adult strongly in continental Europe during the years prior to World War II.[8] After the state of war, Tinbergen moved to the University of Oxford, and ethology became stronger in the United kingdom, with the additional influence of William Thorpe, Robert Hinde, and Patrick Bateson at the Sub-department of Animal Behaviour of the University of Cambridge.[x] In this menstruum, too, ethology began to develop strongly in North America.

Lorenz, Tinbergen, and von Frisch were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1973 for their work of developing ethology.[11]

Ethology is now a well-recognized scientific subject area, and has a number of journals roofing developments in the subject, such every bit Creature Behaviour, Beast Welfare, Practical Fauna Behaviour Science, Animate being Knowledge, Behaviour, Behavioral Ecology and Ethology: International Periodical of Behavioural Biology. In 1972, the International Order for Homo Ethology was founded to promote exchange of knowledge and opinions concerning human behaviour gained by applying ethological principles and methods and published their journal, The Human Ethology Bulletin. In 2008, in a paper published in the journal Behaviour, ethologist Peter Verbeek introduced the term "Peace Ethology" as a sub-discipline of Human Ethology that is concerned with issues of human conflict, disharmonize resolution, reconciliation, war, peacemaking, and peacekeeping behaviour.[12]

Social ethology and recent developments [edit]

In 1972, the English ethologist John H. Cheat distinguished comparative ethology from social ethology, and argued that much of the ethology that had existed so far was really comparative ethology—examining animals as individuals—whereas, in the futurity, ethologists would need to concentrate on the behaviour of social groups of animals and the social structure within them.[xiii]

E. O. Wilson's book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis appeared in 1975,[xiv] and since that time, the report of behaviour has been much more concerned with social aspects. It has too been driven by the stronger, merely more sophisticated, Darwinism associated with Wilson, Robert Trivers, and Westward. D. Hamilton. The related development of behavioural environmental has besides helped transform ethology.[fifteen] Furthermore, a substantial rapprochement with comparative psychology has occurred, and so the mod scientific study of behaviour offers a more or less seamless spectrum of approaches: from animal cognition to more than traditional comparative psychology, ethology, sociobiology, and behavioural environmental. In 2020, Dr. Tobias Starzak and Professor Albert Newen from the Plant of Philosophy II at the Ruhr Academy Bochum postulated that animals may have beliefs.[16]

Relationship with comparative psychology [edit]

Comparative psychology likewise studies animal behaviour, simply, as opposed to ethology, is construed as a sub-topic of psychology rather than as i of biological science. Historically, where comparative psychology has included research on animal behaviour in the context of what is known most human psychology, ethology involves research on animal behaviour in the context of what is known about animal anatomy, physiology, neurobiology, and phylogenetic history. Furthermore, early comparative psychologists concentrated on the study of learning and tended to enquiry behaviour in artificial situations, whereas early ethologists concentrated on behaviour in natural situations, disposed to depict information technology every bit instinctive.

The two approaches are complementary rather than competitive, only they do effect in different perspectives, and occasionally conflicts of opinion nearly matters of substance. In addition, for most of the twentieth century, comparative psychology developed most strongly in North America, while ethology was stronger in Europe. From a practical standpoint, early comparative psychologists concentrated on gaining extensive knowledge of the behaviour of very few species. Ethologists were more than interested in understanding behaviour across a broad range of species to facilitate principled comparisons across taxonomic groups. Ethologists take made much more apply of such cross-species comparisons than comparative psychologists have.

Instinct [edit]

Kelp gull chicks peck at red spot on mother's beak to stimulate regurgitating reflex

The Merriam-Webster lexicon defines instinct as "A largely inheritable and unalterable trend of an organism to make a complex and specific response to environmental stimuli without involving reason".[17]

Fixed action patterns [edit]

An important evolution, associated with the proper noun of Konrad Lorenz though probably due more to his teacher, Oskar Heinroth, was the identification of fixed activity patterns. Lorenz popularized these as instinctive responses that would occur reliably in the presence of identifiable stimuli called sign stimuli or "releasing stimuli". Stock-still activity patterns are now considered to be instinctive behavioural sequences that are relatively invariant inside the species and that nigh inevitably run to completion.[18]

Ane example of a releaser is the beak movements of many bird species performed by newly hatched chicks, which stimulates the mother to regurgitate food for her offspring.[19] Other examples are the classic studies past Tinbergen on the egg-retrieval behaviour and the furnishings of a "supernormal stimulus" on the behaviour of graylag geese.[twenty] [21]

1 investigation of this kind was the study of the waggle dance ("dance language") in bee communication by Karl von Frisch.[22]

Learning [edit]

Habituation [edit]

Habituation is a elementary form of learning and occurs in many animal taxa. It is the process whereby an beast ceases responding to a stimulus. Ofttimes, the response is an innate behaviour. Substantially, the animal learns non to reply to irrelevant stimuli. For example, prairie dogs (Cynomys ludovicianus) give alarm calls when predators approach, causing all individuals in the group to quickly scramble down burrows. When prairie canis familiaris towns are located most trails used by humans, giving alert calls every time a person walks by is expensive in terms of time and energy. Habituation to humans is therefore an of import adaptation in this context.[23] [24] [25]

Associative learning [edit]

Associative learning in brute behaviour is any learning process in which a new response becomes associated with a detail stimulus.[26] The starting time studies of associative learning were fabricated by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov, who observed that dogs trained to acquaintance nutrient with the ringing of a bell would salivate on hearing the bell.[27]

Imprinting [edit]

Imprinting enables the young to discriminate the members of their own species, vital for reproductive success. This important blazon of learning only takes identify in a very limited menstruation of time. Konrad Lorenz observed that the immature of birds such as geese and chickens followed their mothers spontaneously from nearly the start twenty-four hour period afterwards they were hatched, and he discovered that this response could be imitated by an arbitrary stimulus if the eggs were incubated artificially and the stimulus were presented during a critical period that continued for a few days after hatching.[28]

Cultural learning [edit]

Observational learning [edit]

Fake [edit]

Imitation is an advanced behaviour whereby an animal observes and exactly replicates the behaviour of another. The National Institutes of Health reported that capuchin monkeys preferred the company of researchers who imitated them to that of researchers who did not. The monkeys not just spent more fourth dimension with their imitators but as well preferred to appoint in a simple task with them even when provided with the option of performing the same chore with a non-imitator.[29] Imitation has been observed in recent research on chimpanzees; not but did these chimps copy the actions of another private, when given a choice, the chimps preferred to imitate the actions of the higher-ranking elder chimpanzee as opposed to the lower-ranking young chimpanzee.[30]

Stimulus and local enhancement [edit]

There are various means animals can learn using observational learning simply without the process of simulated. I of these is stimulus enhancement in which individuals become interested in an object equally the event of observing others interacting with the object.[31] Increased interest in an object tin result in object manipulation which allows for new object-related behaviours by trial-and-error learning. Haggerty (1909) devised an experiment in which a monkey climbed up the side of a cage, placed its arm into a wooden chute, and pulled a rope in the chute to release food. Another monkey was provided an opportunity to obtain the nutrient after watching a monkey go through this process on iv occasions. The monkey performed a unlike method and finally succeeded afterward trial-and-mistake.[32] Another case familiar to some true cat and dog owners is the power of their animals to open doors. The activeness of humans operating the handle to open up the door results in the animals becoming interested in the handle and and then by trial-and-mistake, they learn to operate the handle and open up the door.

In local enhancement, a demonstrator attracts an observer's attention to a item location.[33] Local enhancement has been observed to transmit foraging information among birds, rats and pigs.[34] The stingless bee (Trigona corvina) uses local enhancement to locate other members of their colony and nutrient resources.[35]

[edit]

A well-documented example of social transmission of a behaviour occurred in a group of macaques on Hachijojima Island, Nippon. The macaques lived in the inland forest until the 1960s, when a grouping of researchers started giving them potatoes on the embankment: soon, they started venturing onto the beach, picking the potatoes from the sand, and cleaning and eating them.[14] About one year after, an private was observed bringing a potato to the ocean, putting it into the water with i hand, and cleaning it with the other. This behaviour was soon expressed past the individuals living in contact with her; when they gave nascency, this behaviour was besides expressed by their young - a grade of social transmission.[36]

Teaching [edit]

Didactics is a highly specialized aspect of learning in which the "teacher" (demonstrator) adjusts their behaviour to increase the probability of the "pupil" (observer) achieving the desired end-result of the behaviour. For instance, orcas are known to intentionally beach themselves to catch pinniped prey.[37] Mother orcas teach their young to catch pinnipeds by pushing them onto the shore and encouraging them to assault the casualty. Because the mother orca is altering her behaviour to assistance her offspring learn to catch casualty, this is bear witness of teaching.[37] Pedagogy is non limited to mammals. Many insects, for instance, accept been observed demonstrating various forms of education to obtain nutrient. Ants, for case, will guide each other to food sources through a procedure chosen "tandem running," in which an ant volition guide a companion ant to a source of food.[38] It has been suggested that the educatee emmet is able to learn this route to obtain nutrient in the future or teach the route to other ants. This behaviour of educational activity is too exemplified by crows, specifically New Caledonian crows. The adults (whether individual or in families) teach their young adolescent offspring how to construct and utilize tools. For example, Pandanus branches are used to extract insects and other larvae from holes within copse.[39]

Mating and the fight for supremacy [edit]

Individual reproduction is the virtually of import phase in the proliferation of individuals or genes inside a species: for this reason, there be circuitous mating rituals, which can exist very complex even if they are frequently regarded as fixed action patterns. The stickleback'due south circuitous mating ritual, studied by Tinbergen, is regarded as a notable case.[forty]

Ofttimes in social life, animals fight for the right to reproduce, every bit well every bit social supremacy. A common case of fighting for social and sexual supremacy is the so-chosen pecking social club among poultry. Every time a group of poultry cohabitate for a certain time length, they institute a pecking gild. In these groups, one chicken dominates the others and can peck without being pecked. A second chicken can peck all the others except the showtime, so on. Chickens higher in the pecking order may at times be distinguished by their healthier appearance when compared to lower level chickens.[ citation needed ] While the pecking order is establishing, frequent and tearing fights tin can happen, but once established, it is broken only when other individuals enter the group, in which case the pecking lodge re-establishes from scratch.[41]

Living in groups [edit]

Several animal species, including humans, tend to alive in groups. Grouping size is a major aspect of their social surroundings. Social life is probably a circuitous and effective survival strategy. It may be regarded as a sort of symbiosis among individuals of the same species: a society is composed of a group of individuals belonging to the same species living inside well-defined rules on food management, role assignments and reciprocal dependence.

When biologists interested in evolution theory first started examining social behaviour, some obviously unanswerable questions arose, such as how the birth of sterile castes, similar in bees, could be explained through an evolving mechanism that emphasizes the reproductive success of every bit many individuals as possible, or why, amongst animals living in minor groups like squirrels, an private would risk its own life to salvage the residue of the group. These behaviours may be examples of altruism.[42] Of course, not all behaviours are altruistic, as indicated by the table below. For example, revengeful behaviour was at one point claimed to have been observed exclusively in Human being sapiens. Nonetheless, other species take been reported to be vengeful including chimpanzees,[43] as well as anecdotal reports of vengeful camels.[44]

| Type of behaviour | Event on the donor | Effect on the receiver |

|---|---|---|

| Egoistic | Neutral to Increases fettle | Decreases fitness |

| Cooperative | Neutral to Increases fettle | Neutral to Increases fitness |

| Altruistic | Decreases fettle | Neutral to Increases fitness |

| Revengeful | Decreases fitness | Decreases fettle |

Altruistic behaviour has been explained by the factor-centred view of development.[45] [46]

Benefits and costs of group living [edit]

One advantage of group living can be decreased predation. If the number of predator attacks stays the same despite increasing prey grouping size, each prey may have a reduced risk of predator attacks through the dilution consequence.[xv] [ page needed ] Further, according to the selfish herd theory, the fitness benefits associated with grouping living vary depending on the location of an individual inside the group. The theory suggests that conspecifics positioned at the centre of a group volition reduce the likelihood predations while those at the periphery will get more vulnerable to attack.[47] Additionally, a predator that is dislocated past a mass of individuals can detect it more difficult to single out one target. For this reason, the zebra's stripes offer not only camouflage in a habitat of tall grasses, simply also the advantage of blending into a herd of other zebras.[48] In groups, prey tin as well actively reduce their predation chance through more than effective defence tactics, or through before detection of predators through increased vigilance.[15]

Another advantage of group living tin be an increased ability to fodder for food. Group members may commutation data about food sources between one another, facilitating the process of resource location.[15] [ page needed ] Honeybees are a notable example of this, using the waggle trip the light fantastic to communicate the location of flowers to the residuum of their hive.[49] Predators also receive benefits from hunting in groups, through using better strategies and being able to take downward larger prey.[15] [ page needed ]

Some disadvantages accompany living in groups. Living in close proximity to other animals can facilitate the manual of parasites and disease, and groups that are too large may also experience greater contest for resources and mates.[50]

Group size [edit]

Theoretically, social animals should accept optimal group sizes that maximize the benefits and minimize the costs of group living. Nevertheless, in nature, about groups are stable at slightly larger than optimal sizes.[15] [ page needed ] Considering information technology generally benefits an individual to join an optimally-sized grouping, despite slightly decreasing the reward for all members, groups may continue to increment in size until it is more advantageous to remain alone than to join an overly total group.[51]

Tinbergen's 4 questions for ethologists [edit]

Niko Tinbergen argued that ethology always needed to include four kinds of explanation in whatsoever instance of behaviour:[52] [53]

- Part – How does the behaviour bear upon the creature'due south chances of survival and reproduction? Why does the animal respond that way instead of another way?

- Causation – What are the stimuli that elicit the response, and how has information technology been modified past contempo learning?

- Development – How does the behaviour modify with age, and what early experiences are necessary for the animate being to display the behaviour?

- Evolutionary history – How does the behaviour compare with similar behaviour in related species, and how might it accept begun through the process of phylogeny?

These explanations are complementary rather than mutually exclusive—all instances of behaviour require an explanation at each of these 4 levels. For example, the role of eating is to acquire nutrients (which ultimately aids survival and reproduction), but the immediate crusade of eating is hunger (causation). Hunger and eating are evolutionarily aboriginal and are found in many species (evolutionary history), and develop early within an organism'due south lifespan (development). It is piece of cake to confuse such questions—for example, to contend that people eat because they're hungry and not to acquire nutrients—without realizing that the reason people experience hunger is considering it causes them to larn nutrients.[54]

Encounter also [edit]

- Anthrozoology

- Behavioral environmental

- Cognitive ethology

- Deception in animals

- Human ethology

- List of aberrant behaviours in animals

References [edit]

- ^ "Definition of ethology". Merriam-Webster . Retrieved ix September 2016.

- ^ "Definition of behaviorism". Merriam-Webster . Retrieved 9 September 2016.

"Behaviourism". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved ix September 2016. - ^ "Guide to the Charles Otis Whitman Collection ca. 1911". www.lib.uchicago.edu . Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- ^ Schulze-Hagen, Karl; Birkhead, Timothy R. (1 January 2015). "The ethology and life history of birds: the forgotten contributions of Oskar, Magdalena and Katharina Heinroth". Journal of Ornithology. 156 (1): nine–18. doi:10.1007/s10336-014-1091-3. ISSN 2193-7206.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1973". Nobelprize.org . Retrieved 9 September 2016.

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1973 was awarded jointly to Karl von Frisch, Konrad Lorenz and Nikolaas Tinbergen 'for their discoveries concerning organization and elicitation of individual and social behaviour patterns'.

- ^ Gomez-Marin, Alex; Paton, Joseph J; Kampff, Adam R; Costa, Rui G; Mainen, Zachary F (28 Oct 2014). "Large behavioral data: psychology, ethology and the foundations of neuroscience" (PDF). Nature Neuroscience. 17 (11): 1455–1462. doi:x.1038/nn.3812. ISSN 1097-6256. PMID 25349912. S2CID 10300952.

- ^ McGreevy, Paul; Boakes, Robert (2011). Carrots and Sticks: Principles of Animal Training. Darlington Printing. pp. xi–23. ISBN978-one-921364-xv-0 . Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Matthews, Janice R.; Matthews, Robert West. (2009). Insect Behaviour. Springer. p. 13. ISBN978-ninety-481-2388-9.

- ^ Keeley, Brian Fifty. (2004). "Anthropomorphism, primatomorphism, mammalomorphism: understanding cantankerous-species comparisons" (PDF). York University. p. 527. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

- ^ Bateson, Patrick (1991). The Development and Integration of Behaviour: Essays in Honour of Robert Hinde. Cambridge University Press. p. 479. ISBN978-0-521-40709-0.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica (1975). Yearbook of science and the future . p. 248. ISBN9780852293072.

- ^ Verbeek, Peter (2008). "Peace Ethology". Behaviour. 145 (11): 1497–1524. doi:ten.1163/156853908786131270.

- ^ Crook, John H.; Goss-Custard, J. D. (1972). "Social Ethology". Annual Review of Psychology. 23 (1): 277–312. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.23.020172.001425.

- ^ a b Wilson, Edward O. (2000). Sociobiology: the new synthesis. Harvard University Press. p. 170. ISBN978-0-674-00089-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Davies, Nicholas B.; Krebs, John R.; West, Stuart A. (2012). An Introduction to Behavioural Ecology (fourth ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN978-i-4443-3949-ix.

- ^ "What it ways when animals have beliefs". ScienceDaily. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Instinct". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ^ Campbell, N. A. (1996). "Chapter l". Biology (four ed.). Benjamin Cummings, New York. ISBN978-0-8053-1957-6.

- ^ Bernstein, W. K. (2011). A Basic Theory of Neuropsychoanalysis. Karnac Books. p. 81. ISBN978-ane-85575-809-4.

- ^ Tinbergen, Niko (1951). The Study of Instinct. Oxford Academy Printing, New York.

- ^ Tinbergen, Niko (1953). The Herring Gull's World. Collins, London.

- ^ Buchmann, Stephen (2006). Letters from the Hive: An Intimate History of Bees, Honey, and Humankind. Random House of Canada. p. 105. ISBN978-0-553-38266-ii.

- ^ Breed, Grand. D. (2001). "Habituation". Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ Keil, Frank C.; Wilson, Robert Andrew (2001). The MIT encyclopedia of the cognitive sciences . MIT Press. p. 184. ISBN978-0-262-73144-7.

- ^ Bouton, M. E. (2007). Learning and beliefs: A contemporary synthesis. Sunderland. Archived from the original on 31 Baronial 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ^ "Associative learning". Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved nine September 2014.

- ^ Hudmon, Andrew (2005). Learning and memory . Infobase Publishing. p. 35. ISBN978-0-7910-8638-4.

- ^ Mercer, Jean (2006). Understanding attachment: parenting, child intendance, and emotional development. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 19. ISBN978-0-275-98217-i.

- ^ "Imitation Promotes Social Bonding in Primates, Baronial 13, 2009 News Release". National Institutes of Health. xiii Baronial 2009. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Horner, Victoria; et al. (19 May 2010). "Prestige Affects Cultural Learning in Chimpanzees". PLOS ONE. 5 (v): e10625. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...510625H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010625. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC2873264. PMID 20502702.

- ^ Spence, 1000. W. (1937). "Experimental studies of learning and higher mental processes in infra-man primates". Psychological Message. 34 (ten): 806–850. doi:10.1037/h0061498.

- ^ Haggerty, Grand. Eastward. (1909). "Imitation in monkeys". Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology. xix (4): 337–455. doi:10.1002/cne.920190402.

- ^ Hoppitt, W.; Laland, M. Due north. (2013). Social Learning: An Introduction to Mechanisms, Methods, and Models. Princeton University Press. ISBN978-1-4008-4650-4.

- ^ Galef, B. Chiliad.; Giraldeau, Fifty.-A. (2001). "Social influences on foraging in vertebrates: Causal mechanisms and adaptive functions". Animate being Behaviour. 61 (1): iii–15. doi:10.1006/anbe.2000.1557. PMID 11170692. S2CID 38321280.

- ^ F.Thou.J. Sommerlandt; Westward. Huber; J. Spaethe (2014). "Social information in the Stingless Bee, Trigona corvina Cockerell (Hymenoptera: Apidae): The use of visual and olfactory cues at the nutrient site". Sociobiology. 61 (4): 401–406. doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v61i4.401-406. ISSN 0361-6525.

- ^ "Japanese Macaque - Macaca fuscata". Blueplanetbiomes.org. Retrieved viii November 2011.

- ^ a b Rendell, Luke; Whitehead, Hal (2001). "Civilization in whales and dolphins" (PDF). Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 24 (2): 309–324. doi:10.1017/s0140525x0100396x. PMID 11530544. S2CID 24052064.

- ^ Hoppitt, W. J.; Brown, One thousand. R.; Kendal, R.; Rendell, Fifty.; Thornton, A.; Webster, M. M.; Laland, K. Due north. (2008). "Lessons from animate being teaching". Trends in Ecology & Development. 23 (ix): 486–93. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.05.008. PMID 18657877.

- ^ Rutz, Christian; Bluff, Lucas A.; Reed, Nicola; Troscianko, Jolyon; Newton, Jason; Inger, Richard; Kacelnik, Alex; Bearhop, Stuart (September 2010). "The Ecological Significance of Tool Use in New Caledonian Crows". Science. 329 (5998): 1523–1526. Bibcode:2010Sci...329.1523R. doi:10.1126/science.1192053. PMID 20847272. S2CID 8888382.

- ^ Tinbergen, Niko; Van Iersel, J. J. A. (1947). "'Displacement Reactions' in the Three-Spined Stickleback". Behaviour. 1 (1): 56–63. doi:10.1163/156853948X00038. JSTOR 4532675.

- ^ Rajecki, D. W. (1988). "Formation of jump orders in pairs of male person domestic chickens". Aggressive Behavior. 14 (6): 425–436. doi:10.1002/1098-2337(1988)14:6<425::Help-AB2480140604>three.0.CO;ii-#. S2CID 141664966.

- ^ Cummings, Marking; Zahn-Waxler, Carolyn; Iannotti, Ronald (1991). Altruism and assailment: biological and social origins . Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN978-0-521-42367-0.

- ^ McCullough, Michael E. (2008). Across Revenge: The Evolution of the Forgiveness Instinct. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 79–fourscore. ISBN978-0-470-26215-3.

- ^ De Waal, Frans (2001). The Ape and the Sushi Primary: Cultural Reflections by a Primatologist . Basic Books. p. 338. ISBN978-0-465-04176-iii . Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (January 1979). "Twelve Misunderstandings of Kin Selection". Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 51 (2): 184–200. doi:ten.1111/j.1439-0310.1979.tb00682.x.

- ^ Ågren, J. Arvid (2016). "Selfish genetic elements and the factor's-middle view of evolution". Electric current Zoology. 62 (6): 659–665. doi:10.1093/cz/zow102. ISSN 1674-5507. PMC5804262. PMID 29491953.

- ^ Hamilton, West. D. (1971). "Geometry for the Selfish Herd". Periodical of Theoretical Biology. 31 (2): 295–311. Bibcode:1971JThBi..31..295H. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(71)90189-v. PMID 5104951.

- ^ "How exercise a zebra'south stripes act as camouflage?". HowStuffWorks.com. 15 April 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ Riley, J.; Greggers, U.; Smith, A.; Reynolds, D. R.; Menzel, R. (2005). "The flying paths of honeybees recruited by the waggle dance". Nature. 435 (7039): 205–207. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..205R. doi:10.1038/nature03526. PMID 15889092. S2CID 4413962.

- ^ Rathads, Triana (29 August 2007). "A Look at Animal Social Groups". Science 360. Archived from the original on viii May 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ Sibley, R. M. (1983). "Optimal group size is unstable". Beast Behaviour. 31 (3): 947–948. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(83)80250-4. S2CID 54387192.

- ^ Tinbergen, Niko (1963). "On aims and methods in ethology". Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 20 (4): 410–433. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1963.tb01161.x.

- ^ MacDougall-Shackleton, Scott A. (27 July 2011). "The levels of analysis revisited". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 366 (1574): 2076–2085. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0363. PMC3130367. PMID 21690126.

- ^ Barrett et al. (2002) Human Evolutionary Psychology. Princeton University Press.

Farther reading [edit]

- Burkhardt, Richard W. Jr. "On the Emergence of Ethology as a Scientific Subject area." Conspectus of History ane.7 (1981).

Animal Behavior Researchers Often Refer,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethology

Posted by: houptannothe.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Animal Behavior Researchers Often Refer"

Post a Comment